Gravitational Waves Unveil The Lightest Black Hole Yet

Header Image: Artistic rendition of a black hole merging with a neutron star. Image credit: LIGO-India/ Soheb Mandhai

Written by The Adler Planetarium’s Astronomer, Dr. Michael Zevin.

Gravitational waves have opened up a new window into our universe. They are a unique messenger that has been crucial in discovering systems of black holes and neutron stars.

In What Are Gravitational Waves: A New Window Into The Universe, I talked about the inauguration of this new and exciting field in astronomy, and left everyone hanging with the start of the 4th observing run in May 2023. But the gravitational-wave community didn’t have to wait very long for the first exciting discovery!

Discovering The Mass Gap Black Hole

On May 29, 2023, gravitational waves were detected from a new type of system. I was fortunate to co-lead the discovery paper of this system on behalf of the almost 2,000 LIGO–Virgo–KAGRA collaboration scientists around the globe.

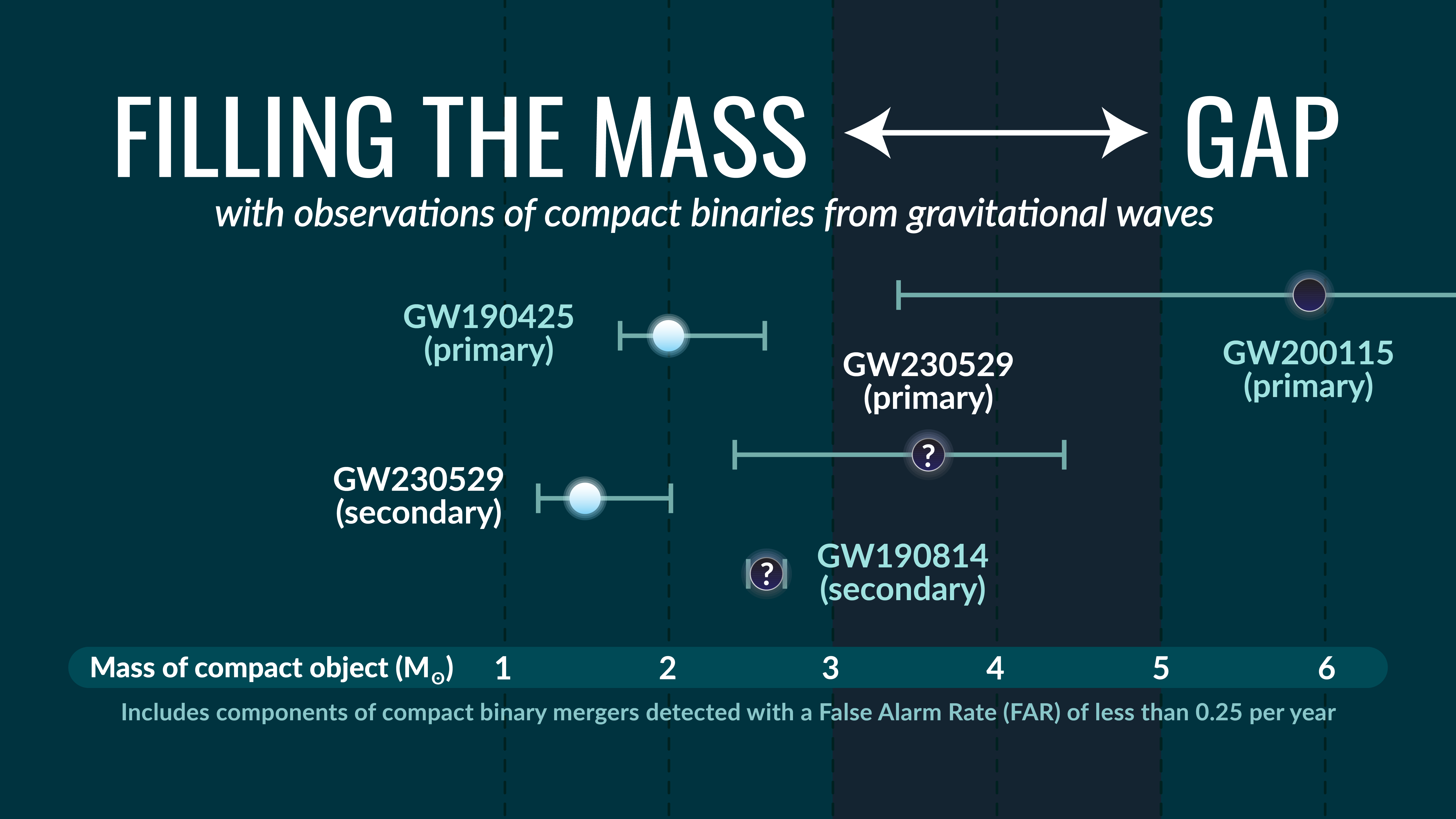

The gravitational-wave event, dubbed GW230529 (“GW” for “gravitational wave” and its phone number “230529” for the year, month, and day of the detection), was seen only by the LIGO detector in Louisiana; all other detectors were either offline or not sensitive enough to see it.

Although we are confident that it is a real astrophysical event and not some source of noise, gravitational wave detectors are somewhat like omnidirectional microphones. Without multiple detectors to triangulate the signal, we couldn’t determine where in the sky it came from.

However, we can tell that the system was about 650 million lightyears away, meaning the gravitational waves were sent out a long, long time before even dinosaurs were around. We could also tell how massive the two objects in the system were, which was the real kicker.

What Is The Mass Gap?

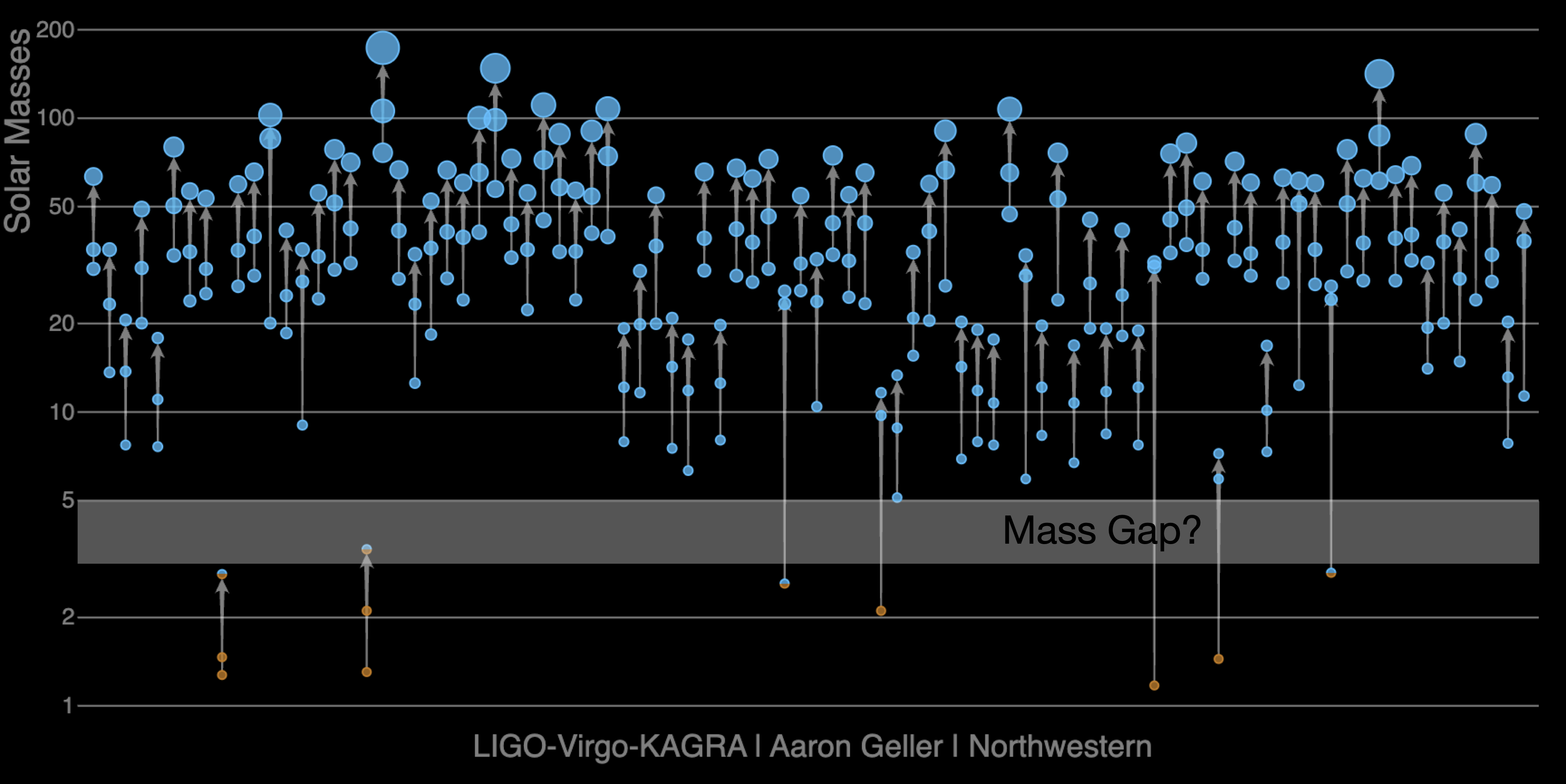

Since the late 1990s, astronomers have hypothesized that there might be a “gap” between the heaviest neutron stars and the lightest black holes. Neutron stars can sustain themselves up to somewhere between two to three times the mass of the Sun before they can’t withstand the force of gravity anymore and collapse into a black hole (the exact “maximum mass” of a neutron star is a hot topic in astrophysics).

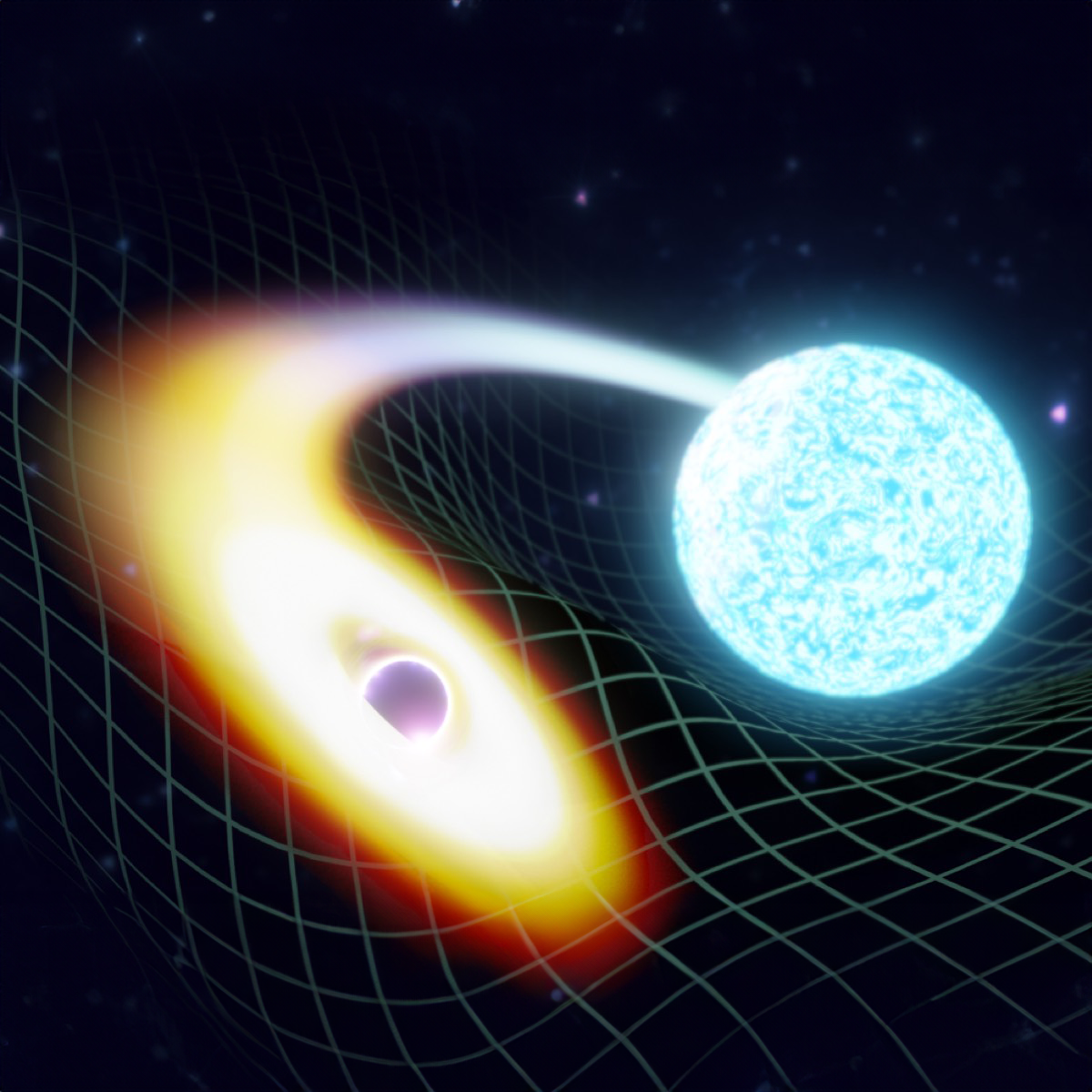

We’ve also indirectly inferred the masses of black holes in our own galaxy—the Milky Way—in systems called X-ray binaries. An X-ray binary is where a black hole is in a binary system with a star and stealing material from it.

Based on how the star moves in the sky, we can tell the mass of the invisible black hole. It turns out that the lightest black holes observed in the Milky Way were no less than five times the mass of the Sun! Therefore, there seems to be a gap in the masses of neutron stars and black holes that is between three–five times the mass of the Sun.

Is there a reason these lightweight black holes don’t form? Astronomers came up with theories about how the supernovae that form black holes can avoid this regime of masses. However, it is also possible that there is something we don’t quite understand about the biases of observing black holes in X-ray binary systems.

A Black Hole In The Mass Gap

The black hole in GW230529 falls squarely in this “mass gap,” with a mass that is likely three–four times the mass of the Sun. This gravitational-wave event is one of the best pieces of evidence that lightweight black holes can exist in nature. The black hole in the system is also in the running for being the lightest black hole ever observed!

Despite how much mass they contain, black holes are amazingly small for their weight. At a few times more massive than the Sun, the black hole we observed could fit comfortably within the city of Chicago! This is wild, considering that we can see the way it distorts spacetime at a distance of 650 million lightyears—about four billion trillion miles.

The lighter object in the system was likely a neutron star. When neutron stars merge with another compact object like a black hole or another neutron star, they can get ripped apart and create a kilonova. Kilonovas are explosions powered by radioactive decay that result in a synthesis of the heavy elements on the periodic table and a stunning light show.

However, if a neutron star merges with a black hole that is too heavy, it will get swallowed whole by the black hole before it can get torn to shreds, without emitting light or synthesizing heavy elements. Although we did not observe a kilonova alongside GW230529 (we couldn’t tell where in the sky it came from, which makes it exceedingly difficult to find an electromagnetic counterpart), the small black hole in the GW230529 system also tells us that black holes can indeed tear apart neutron stars before swallowing them whole.

More exciting gravitational-wave discoveries are on the horizon. Until then, keep looking up!

Learn More From Our Astronomers

Get more space with Adler Planetarium astronomers on our YouTube Channel! Ever wondered what dark matter actually is, or if we’re living in a simulation? Hear directly from our experts on some of the most commonly asked—and not so commonly asked—astronomy questions.