Astronomy and Space Facts From A to Z

Header Image: The outside of the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, IL at sunset in the fall.

When you were a kid, you probably learned your ABC’s using stuff like, “A is for…apple” or “B is for…bee” or “C is for…cat” to represent each letter.

While those options are all fine and good and cute, what if you learned your ABC’s only using stuff related to space?? Now that would have been pretty cosmic!

Check out the ABC’s of Space from the Adler Planetarium to learn about a variety of space science topics, cool telescopes, programs at the planetarium, and more.

A is for…Aquarius Project

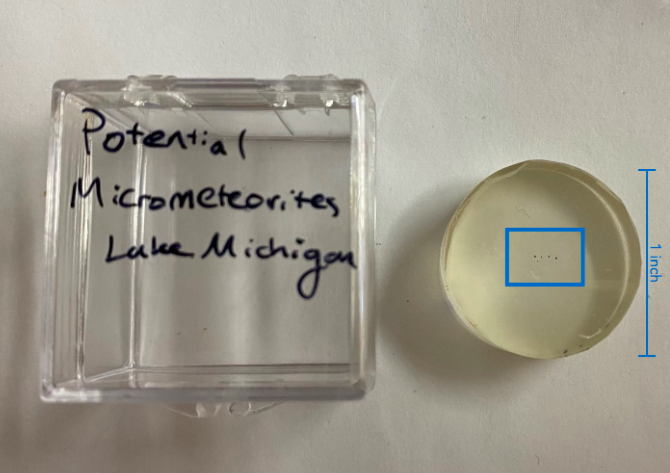

Story time: back in February 2017 (at approximately 1:30 am on a Monday) a 600-pound meteorite broke through our planet’s atmosphere and crashed into Lake Michigan. This space rock sparked the creation of the Aquarius Project—aka the most epic Adler Teen led underwater meteorite hunt EVER!

Over the last five years, Adler Teens worked with scientists from the Adler Planetarium, Field Museum, Shedd Aquarium, and NASA to find fragments from this car-sized space rock.

They worked together to build a submersible 200-pound sled (named Starfall) to collect samples 275 feet below the surface of the water, adapted a remotely operated vehicle with a powerful rare-Earth magnet and camera to capture more potential fragments, helped sift through everything they found, and then sent it all off to the lab for testing!

So, did the team find space rocks??

Yes, yes they did! At least FIVE micrometeorites were found by the Aquarius Project team! All of these rocks are about the size of a grain of sand, so they are incredibly small. Even though the team originally set out to find space rocks from a specific astronomical event, these micrometeorites all came down to Earth from different sources, meaning the team found rocks from a few different asteroids. Pretty cool, right?!

We’re so proud of our stellar Adler Teen alums and everything the Aquarius Project team accomplished!

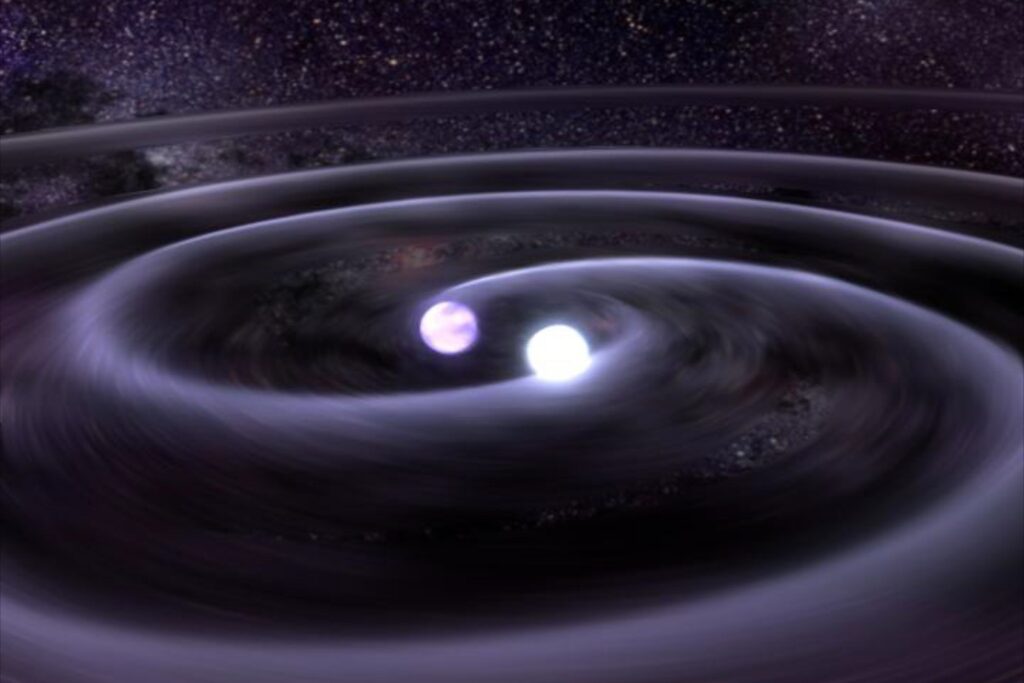

B is for…Binary Stars

Picture this—you’re looking at a beautiful sunset, but instead of one sun, there are two! Or maybe you’re a Star Wars fan, and the scene of Luke Skywalker staring at the sunset on Tatooine comes to mind. (If you haven’t seen it, give it a quick Google search, it’s a pretty sun-tastic sight!)

Binary stars—or binary systems—are two stars that are bound together by gravity and orbit around each other. Though we can’t tell most times when we look up, about 85% of stars are in binary systems! The brightest star in our sky, Sirius, is a binary star system consisting of Sirius A and Sirius B.

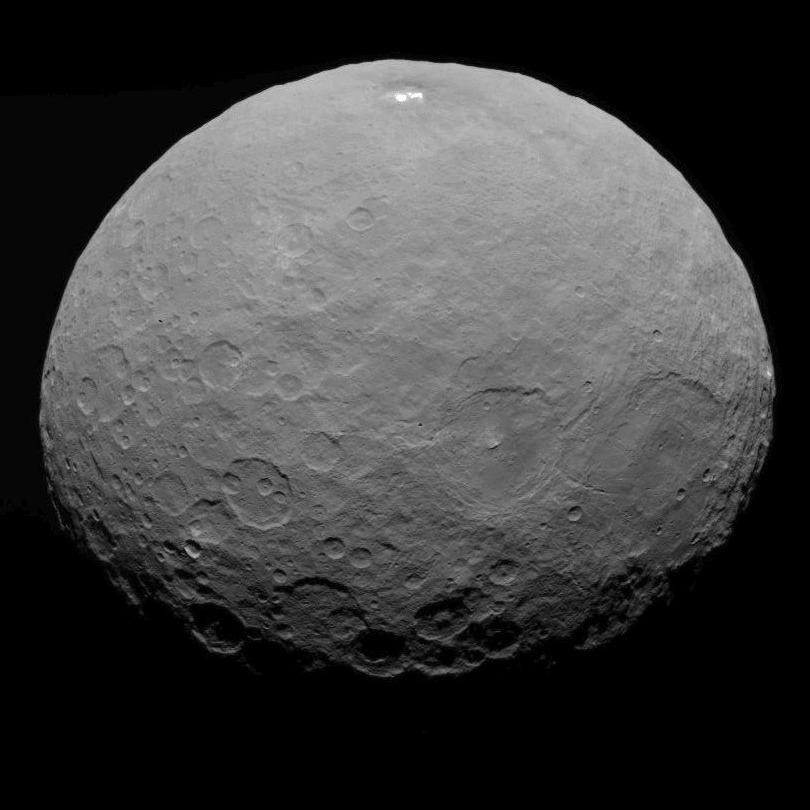

C is for…Ceres

This is no ordinary space rock—this is a dwarf planet.

Discovered in 1801, Ceres was actually considered an asteroid until it was classified as a dwarf planet in 2006. Ceres resides in our solar system’s asteroid belt, so it’s about 241 million miles from the Sun.

Compared to its couple million asteroid neighbors, Ceres is huge! It makes up 1/4 of the asteroid belt’s total mass.

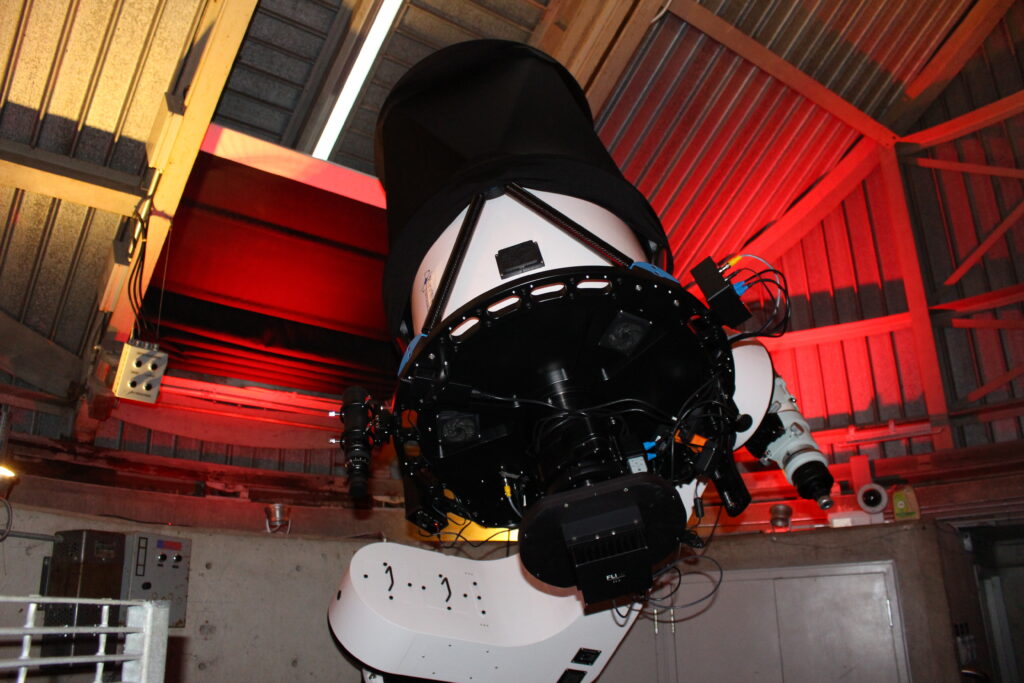

D is for…Doane Observatory

Tucked next to the shores of Lake Michigan and behind the Adler Planetarium, sits the Doane Observatory! It is home to the largest telescope available to the public in the Chicagoland area.

The Doane was built in 1977 with the goal of getting visitors up close to telescopes and looking up at the night sky. Over 40 years later and we are still connecting people to the universe right here in the observatory! The current telescope inside gathers over 7,000 times more light than the unaided eye, which means YOU could come see celestial objects that are trillions of miles away. How cool is that?

If you stop by on a Wednesday night, you might just get the chance to look through that gigantic telescope!

E is for…Europa

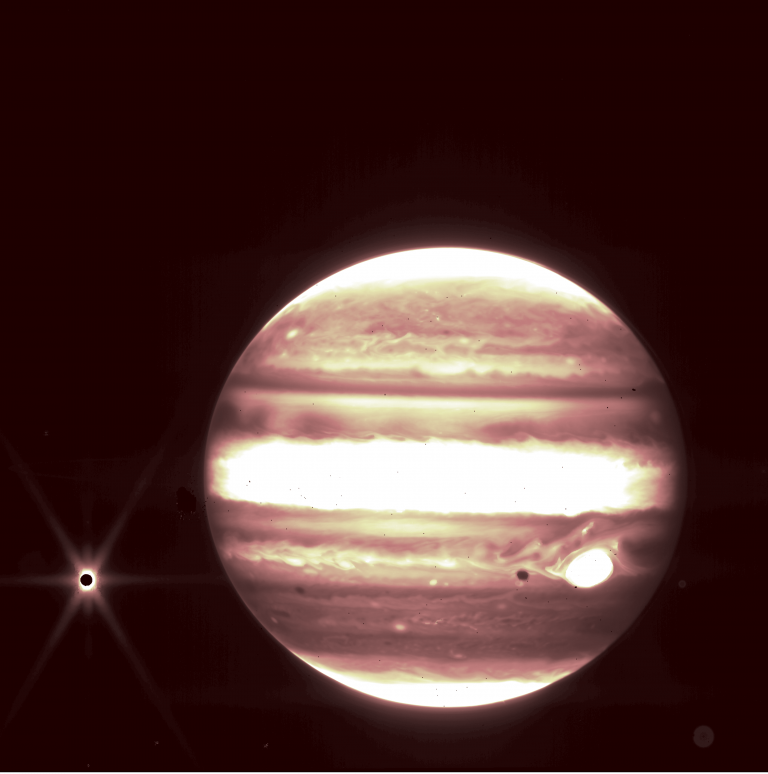

Recognize this planet? We’ll give you a hint—this is the biggest planet in our solar system that has a huge spot (aka hurricane-like storm) on its surface.

If you’re immediately thinking Jupiter…you’re totally correct! So, if this is Jupiter, what’s that dot to its left? Say hello to Europa!

The JWST took this test infrared image of Jupiter and also caught one of its moons—Europa—in the frame as well!

Europa is one of at least 80 moons that orbit the gas giant. It is known as one of the four Galilean moons because it was discovered by Galileo Galilei in the early 1600s. What makes Europa special? There is most likely a huge ocean right below its icy surface. Europa has potentially more water than all of Earth’s oceans combined!

F is for…Flat Earth

But the Earth isn’t flat. We have the receipts!

The theory that the Earth is flat has been scientifically disproven through many different scientific experiments and processes. Here are just a few reasons we know our home planet is a sphere!

- The shape of Earth’s shadow on the Moon during a lunar eclipse is curved.

- When you are looking at an approaching boat on the water, it does not just suddenly appear as a whole boat—if it did, that would be a good determining factor that the Earth is flat! Instead, from a distance, you will see the top of the ship first, then more of it in the middle, and then the bottom of it as it gets closer and closer.

- Planes regularly fly for long distances and don’t fall off any edges. In 1986, a plane flew nonstop around the entire planet and arrived back at its starting point, which would be impossible if Earth had edges and was flat.

- If Earth were flat, the Sun would rise and set at the same time for everyone and there would be no need for timezones. Central Standard Time who?

- The center mass of a flat plane is in the center of the plane. That means gravity would pull anything on the surface toward the middle of the plane. If Earth was flat and you dropped a ball, it would fall sideways towards wherever the center of the Earth plane is. But, because Earth is round, and gravity pulls towards its middle, when you drop a ball, it falls down toward the middle of the Earth!

G is for…Gneiss

The metamorphic rock known as Morton gneiss holds a very special place in our hearts. Why? Because our dodecagon building is covered from top to bottom in it!

Usually, if you ever see a building made out of gneiss, it was most likely built in the 20s or 30s—we opened in 1930! It has an incredibly distinctive look caused by intense heat and pressure warping all of the different layers of rock together.

Next time you visit us, impress your fellow stargazers with this fun fact regarding the Morton gneiss you’re about to walk on to get up to our front doors: this rock is 3.5 billion years old, so it’s some of the oldest rock you’ll ever see or touch.

H is for…High Altitude Ballooning

High-altitude balloons take quite the stellar trip as they are filled with helium or hydrogen, float away into the stratosphere and reach up to 100,000 feet above us!

I is for…Impact Crater

Have you ever seen that space rock in Our Solar System exhibit? It’s a very small portion of a meteorite that struck our planet 50,000 years ago. Known as the Canyon Diablo meteorite, it was a part of the space rock that created Barringer Crater (also called Meteor Crater) in northeastern Arizona.

Meteor Crater is about .75 miles wide—if you live in Chicago, this is pretty much as wide as the distance from the Adler Planetarium to Lake Shore Drive! This impact crater is also about 600 feet deep.

J is for…JWST

After almost 20 years of anticipation, the most powerful space telescope ever created—the JWST—has begun to show us the universe like we’ve never seen it before. Read our blog to learn why we will use only the telescope’s initials when we talk about it.

K is for…Kuiper Belt

Extending past Neptune, the Kuiper Belt is the area of space leftover from the formation of our solar system!

Represented by the yellow lines in this space visualization are the orbits of Kuiper Belt objects. These objects—which are shown as dots—can be bits of rock, ice, comets and dwarf planets.

As scientists continue to study this donut-shaped ring containing thousands of icy bodies, they will get a better understanding of how planets form!

L is for…Light Spectrum

Any guesses as to what you’re looking at in the photo above?

The bright dot in the lower left corner is Polaris—more commonly known as the North Star! If you look close to the left of that, there is an even tinier dot which is Polaris’ companion star, Polaris Ab. It’s so close to Polaris that our eyes normally can’t split them into two separate stars.

This image was taken through our Doane Observatory telescope with a diffraction grating filter. This filter splits the light being received into the different colors that make up the star. So if you combined that long strip of colors—the light spectrum— together into one, you would get the color you see from the star!

Data from these light spectrums is very useful to astronomers as it can reveal characteristics of a star like its temperature, the gasses it’s made of, and other information that allows them to classify the star.

M is for…Mae Jemison

On September 12, 1992, Dr. Mae Jemison became the first African American woman to fly into space!

As the mission specialist on Space Shuttle Endeavour, she spent a total of eight days in space. During the 127 times Endeavour orbited our planet, she did several experiments for NASA. Here you can see her having a pressurization leak check done on her spacesuit before takeoff.

Fun fact: she is a former resident of Chicago!

Have A Suggestion?

Have a letter you want to suggest? DM us on your favorite social media channel with a suggestion for the remaining letters!